Coq au Vin: Proof That Tough Old Chicks Were Made for Wine

- Sylvia Fonalka

- 2 days ago

- 13 min read

Every now and then, when the grocery gods are truly smiling, you’ll spot whole hens quietly tucked away at the back of the store or at the market. When I see them (usually at Save-On-Foods, sold in pairs under the very honest name Mature Small Stewing Hen), I grab them without hesitation. They’re modestly priced for birds with this much life experience, and trust me: that experience shows up in the flavour.

And a quick PSA while we’re here: don’t be fooled by the Cornish hen. That tiny, photogenic foreign bird is not a hen at all, but a very young chicken with good PR.

The real stewing hens, on the other hand, are not here for weeknight shortcuts. They’re bold, full-bodied, and built for the dishes I love most: long-simmered, deeply rich soups and braises… or, today’s chosen indulgence, Coq au Vin.

Coq au Vin (kok-oh-vehn, with that unmistakably nasal French ehn) translates to rooster in wine. Traditionally or historically, yes, an actual rooster. Tough, muscular, and deeply resistant to tenderness unless thoroughly humbled by hours in a pot and a generous amount of wine.

To be clear: a proper hen, or even a rooster, in the right hands, is superior. I know this because one of my best childhood food memories is my grandmother’s rooster paprikás: deeply savoury, slow-cooked, and worth every minute it demanded. When treated with respect and time, those birds deliver real flavour.

But this is the 21st century. We have schedules and far less patience. So we reach for a good chicken instead, faster, gentler, and far more cooperative, while keeping the soul of the dish quasi intact.

The method remains the same: long, slow braising with wine (often Bourgogne), bacon or lardons, onions, and mushrooms. Nothing flashy, just time, flavour, and the understanding that some things, much like people, get better when they’re allowed to simmer.

Modern Poultry Economics

Hen availability is rare (roosters are basically mythical), and no, it’s not a conspiracy, it’s modern poultry economics. As chickens age, their muscles work harder, build character, and load up on connective tissue.(Relatable). A stewing hen can be 10 months to three years old, versus the six-to-eight-week lifespan of broiler chickens. The result? Meat that refuses to be rushed and demands time, moisture, patience, and ideally, wine. Frankly, same.

The industry prefers speed and efficiency: broilers for fast, plump meat, laying hens for eggs - not dinner. Once egg production slows (around 18 months), hens usually vanish into processed foods instead of grocery carts. It’s more profitable that way, even if flavour loses.

Which is a shame, because these hens have depth and stories to tell—if you give them time. And wine. Always wine. When you find one, grab it. They were made for dishes like Coq au Vin.

Coq au Vin - un peut d'histoire

Coq au Vin is unmistakably French, originating in Bourgogne (Burgundy, for those not currently holding a glass), it sits at the intersection of rustic French cooking and very good storytelling. It began, quite sensibly, as a way to make tough old roosters edible: through the magic of time, wine, and patience.

Market poultry display in Dijon | Fifteenth century half-timbered houses in Dijon | Beaujolais wine region

Somehow grew into one of France’s most celebrated dishes. Its rise to global fame came much later, thanks largely to Julia Child in the 1960s, when Coq au Vin crossed the Atlantic and became a household name, but its roots stretch far deeper, possibly all the way back to ancient Gaul or Rome.

Legend has it that during the Roman occupation of Gaul, the Gauls (ancient Celts of modern France, Belgium, and nearby parts: Iron Age, iron wills, excellent moustaches) sent a rooster to Julius Caesar as a cheeky challenge. Caesar’s response? He had his cook braise the bird in wine and send it back, deliciously defeated. True or not, the story sticks and it fits what we know: the Romans were already cooking poultry in wine, so the idea has been simmering for a very long time.

Sadly, the Roman legions crushed the tribes, and Gaul became a Roman province.

The rooster, however, endured as a symbol: born from a Roman pun (gallus meaning both "Gaul" and "rooster") that the Gauls eventually reclaimed as a badge of defiance. And if you think that ancient insult didn’t age well, consider this: the French national football team proudly wears the Coq Gaulois on their blue jerseys right alongside the World Cup stars. From Roman mockery to global swagger. Not bad for a bird that started out as a joke.

By the Middle Ages and into early modern France, Coq au Vin was firmly a farmhouse dish. Old roosters or hens weren’t tender, but they were plentiful, and slow cooking in wine turned stubborn muscle into something deeply satisfying.

What started as peasant cooking evolved into one of France’s most iconic dishes, the recipe began appearing in more formal cookbooks in the 19th century.

Though Bourgogne claims the classic version, every region has put in its two cents, swapping in local wines like Riesling in Alsace or even Champagne in, well, Champagne, bien sûr. Old, comforting, and still deeply loved, Coq au Vin proves that in France, patience, good wine, and a little tradition go a very long way.

Bleu-Blanc-Rouge of Chickens: The Bresse Poultry

This post about a French chicken dish would be borderline ignorant if it didn’t at least tip its hat to Bresse chicken. When France talks about chicken, this is the chicken, the benchmark, the legend, the one all other birds are quietly compared against and usually lose. Leaving it out would be like writing about Champagne without bubbles or Burgundy without terroir.

Simply put: if you’re talking French poultry, Poulet de Bresse deserves a seat at the table.

Bresse chicken, often crowned "the Queen of All Poultry," is instantly recognizable by its chic French tricolour look: blue legs, white feathers, red comb! It’s basically walking around in a tiny national flag.

Its meat is famously succulent, rich, and deeply flavourful, the kind of chicken that makes you question every bland bird you’ve ever cooked.

Granted AOC status in 1957, Poulet de Bresse comes with some very serious credentials. The Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée statues guarantees that these chickens come from one specific place and are raised using strict, traditional methods. Think terroir, paperwork, and no shortcuts, all in the name of flavour. True Bresse chickens must be raised in the historic Bresse region of eastern France (in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté), roam free for at least four months, and dine on a refined menu of grass, insects, cereals, and yes, milk. Production is tightly regulated, which means they make up only a tiny fraction of France’s poultry output.

In France, Bresse chicken is easy to find at quality butchers and markets. Outside France, it’s rare, occasionally appearing frozen in the U.S. or on high-end menus, usually at eye-watering prices.

In Canada, availability is nearly nonexistent. But! Enter the Canadian Bresse (aka Canadian Gauloise). Raised on a few farms across the country from authentic Bresse genetics, these birds grow slower, spend more time outdoors, and pack far more flavour than your average supermarket chicken.

You’re unlikely to spot one casually lounging on a grocery store shelf - this is more gourmet restaurant territory - but it’s a very welcome solution. And if all else fails, consider this your official excuse for a culinary pilgrimage to France. 🐔🇫🇷

What Wine To Use

YES, back to wine 🍷 - the most important supporting character.

Sorry, I got briefly distracted by chickens, moustaches, and emperors (things I deeply enjoy and will absolutely derail me every time).

Now, focus! Wine. The sauce depends on it.

When making Coq au Vin, the wine isn’t just an ingredient: it’s the backbone of the whole dish. So choose wisely. You want a good dry red wine that you’d happily pour into a glass and drink. If you wouldn’t sip it, don’t simmer with it. The rule is simple: wine quality matters, because whatever goes into the pot gets louder as it cooks. Long simmering doesn’t mellow bad wine, it amplifies it.

The classic choice is Pinot Noir (from Bourgogne, preferably). It’s traditional for a reason: light, earthy, gently fruity, and perfectly suited to chicken and mushrooms. Think elegance, not muscle.

Beaujolais (also Bourgogne), made from Gamay, is another excellent option: bright, juicy, and forgiving.

If you’re in the mood for something a little bolder, Côtes du Rhône brings deeper, spicier notes that turn the sauce into a warm hug.

You can use Merlot or Cabernet Sauvignon in a pinch, but tread lightly. Merlot behaves. Cabernet… likes to make itself known. Too tannic, and your sauce may start bossing you around.

That said, rules are meant to be bent with good judgment, and a corkscrew.

Beaujolais Villages

No, I’m not completely reckless (or rich) - I went with a Beaujolais-Villages for the sauce. The bottle that went into the stew was a more modest, perfectly respectable Beaujolais, specifically the Joseph Drouhin Beaujolais-Villages, made from 100% Gamay.

Bright, fresh, and wonderfully approachable, this classic Beaujolais offers vibrant aromas of red cherry, raspberry, and violet, with a silky texture and soft tannins that make it ideal for cooking. Its lively acidity and juicy red-fruit character bring depth and balance to the sauce without overpowering the dish. With an alcohol level around 12.5% and an accessible price point typical of "Villages" wines, it’s an excellent, affordable choice that proves you don’t need an expensive bottle to achieve beautiful flavour in the kitchen.

By the way, a quick Maison Joseph Drouhin spotlight: this legendary Burgundy négociant, founded in 1880 and still family-run by the fourth generation, has a portfolio that stretches far beyond our humble Beaujolais Villages. Some of their notable wines and estates include Clos des Mouches, a famous Premier Cru in Beaune producing both stunning Pinot Noir and Chardonnay; parcels in Grand Cru sites like Musigny, Grands Échézeaux, and Bâtard-Montrachet; the Drouhin-Vaudon Chablis estate, known for its mineral-driven Chardonnays; and even Oregon estates, including the original Dundee Hills vineyard and Roserock in Eola-Amity Hills. For our stew, we went modest—but hey, the pedigree is there! A perfectly respectable, totally affordable, and just right for turning your stew into something rich and silky without breaking the bank.

Juliénas, Beaujolais

The bottle we poured with dinner was a proper Juliénas AOC. Priorities.

Made also from Gamay, grown on granite-rich soils, it brings structure without heaviness: dark cherry, crushed berries, a little iron, a little earth. Juliénas sits at the northern edge of Beaujolais, just south of Burgundy proper: Bourgogne-adjacent, geographically and philosophically, often showing more backbone and savoury depth than its northern neighbours.

That granite-driven tension and bright acidity make it ideal for Coq au Vin: enough grip to stand up to wine-braised chicken, enough lift to keep the dish from slipping into stew fatigue.

Juliénas itself is the northernmost of the Beaujolais crus.

I bravely investigated this fact with multiple glasses - consider this your excuse to read my illustrated Beaujolais travel story here.

To circle back to the Roman dictator we all love to mock, Juliénas is named for Julius Caesar himself, with villages founded during his reign (100–44 BCE). Yes, that Julius. Sandals, ego, legions, the whole production.

If you’ve ever watched an Astérix movie, skimmed the comics, or accidentally stayed awake in a history class, you’ll know how this went: Rome occupied Gaul (modern-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, plus bits of Germany and Italy), built roads, imposed order, and very politely "introduced" Roman culture. The Gauls, naturally, resisted, loudly, stubbornly, and with excellent honey mead. Colonization is complicated like that. But wine? Wine is universal.

So, here we are, cooking a French dish born of Gaulish defiance, paired with a wine named after Julius Caesar - the guy who conquered the Gauls. Poetic? Sure. Ironic? Definitely. Delicious? Absolutely. It’s French, through and through.

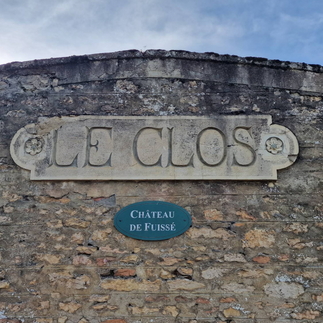

Winery: Château-Fuissé

Nestled in the heart of the Mâconnais, Château-Fuissé is one of those estates that wine lovers quietly obsess over. With 40 hectares of vines spread across more than 100 tiny plots, it’s basically a terroir patchwork quilt - in the best possible way. Each climat brings its own mood, texture, and personality, and thanks to an almost uncanny understanding of their soils, Château-Fuissé turns this complexity into wines that are layered, expressive, and impossible to find boring.

Le Clos is the crown jewel of Château-Fuissé: a legendary 2.7-hectare walled vineyard that literally wraps around the château and, as of the 2020 vintage, proudly wears its Premier Cru monopole status within Pouilly-Fuissé. Now, full disclosure, this is not our wine parcel (we’re firmly in Gamay territory), and this one very much belongs to the sanctified, altar-worthy world of Chardonnay. But it’s far too special not to mention. With its gentle east-facing slope and a fascinating mix of clay, marl, and flinty limestone soils, this tiny plot produces old-vine Chardonnay (some planted in the 1920s) that’s powerful yet elegant, layered with ripe stone fruit, citrus, honey, butter, vanilla, and a mineral finish that just keeps going. It’s built to age and shines with lobster, scallops, or Bresse poultry. Basically, this is Chardonnay behaving at its absolute best, and we tip our hats to it.

Winemaker website: https://chateau-fuisse.fr | Photo credit: @chateau.fuisse

A true family affair

The story starts back in 1862 with Claude Bulland, and five generations later, the estate is now in the hands of Antoine Vincent. Every generation has added its own chapter - respecting tradition, embracing smart innovation, and gently nudging things forward without losing the plot (or the roots). Think heritage with curiosity, precision with personality, and just the right amount of Burgundian stubbornness. The kind that ages very, very well.

Château-Fuissé Juliénas 2022

Poured into the glass, this Juliénas flashes a deep ruby red with a little sparkle, like it knows it’s about to be admired.

The nose is all fresh flowers and juicy red fruit: peonies flirting with wild strawberries, red currants, and raspberries, with just a whisper of spice tagging along.

On the palate? Smooth and elegant. Soft red plum and strawberry glide in first, backed by lively acidity that keeps everything fresh and vibrant. Then come the surprise cameos: a hint of bakery warmth, a touch of ground coffee, and a dash of white pepper. The finish is crisp, gently mineral, slightly licorice-tinged.

Made from 100% Gamay in the granite-rich soils of Juliénas, and vinified in stainless steel to keep things bright and pure, this wine is polished without being precious.

At 14.5% ABV, it’s lively, food-loving, and dangerously easy to keep refilling.

Pair it with roast chicken, turkey, red meat, charcuterie boards that accidentally turn into dinner, tomato-y pasta, cozy pies, cheeses, or even grilled fish or:

Coq au Vin (French Red Wine Braised Chicken)

Serves 4-6

Preparation time: 1 hour, plus marinading time (12 hour) | Cooking time: 1 hour 15 minutes

A timeless, deeply comforting dish: tender chicken slowly braised in red wine, finished with bacon lardons, mushrooms, and glossy pearl onions.

Ingredients

Chicken/Hen

1 whole chicken or hen (1.2 kg / 2.6 lb), cut into 6–8 pieces

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Ca va, ça va! You can also use drumsticks, thighs, or both, but for the love of juiciness, don’t just stick to the breast. Sacré bleu, non. Trust me, the whole bird is where the magic happens.

Marinade

1 carrot, sliced

1 onion, sliced

1 celery stalk, sliced (optional)

2 garlic cloves, peeled

1 bouquet garni (1–3 bay leaves, 1 sprig thyme, 1 sprig rosemary)

1 tsp / 5 g black peppercorns

1 bottle (750 ml / 3 cups) dry red wine (preferably Bordeaux)

For Cooking

1½ tbsp / 20 ml olive oil or lard

⅓ cup / 50 g all-purpose flour

2 cups / 500 ml chicken stock

1 tbsp / 15 ml tomato paste

2 tbsp / 30 ml cognac or brandy (optional)

1 bay leaf

Lardons

3½ oz / 100 g bacon, rind removed and cut into batons

Mushrooms & Pearl Onions

3½ oz / 100 g button mushrooms, quartered

20 fresh pearl onions, peeled (not pickled)

3½ tbsp / 50 g butter

To Finish

½ bunch flat-leaf parsley, finely chopped

** How to Cut Up a Whole Chicken (Quick Guide)

Remove legs: Cut skin between leg and body, pull back to pop the joint, and cut through.

Separate thigh & drumstick: Cut along the natural fat line.

Remove wings: Lift wing, find the joint, and cut through.

Breast & back: You can cut out the backbone and save for stock or leave it on with each breast halves. Depending in the size of your bird, cut each half into 2–3 pieces.

Instructions

1. Marinate the Chicken/Hen

Place the chicken/hen pieces in a large bowl with the carrot, onion, celery, garlic, bouquet garni, peppercorns, and red wine. Cover and refrigerate for at least 2 hours, or up to 12 hours for deeper flavor.

2. Prepare for Cooking

Preheat the oven to 200°C / 400°F. Position a rack in the middle of the oven to accommodate a large Dutch oven with its lid.

Remove the chicken/hen and vegetables from the marinade and pat dry. Discard the herbs.

Do not discard the wine, for the love of all things delicious.

Strain the marinade into a saucepan and reserve.

3. Brown the Chicken

Heat the oil or lard in a large ovenproof casserole over medium-high heat. Brown the chicken pieces on all sides, working in batches if necessary. Remove and set aside.

4. Build the Base

In the same casserole (all the flavour is here), add the bacon and cook until lightly browned. Stir in the tomato paste and cook for 1 minute.

Deglaze with the cognac, scraping up the browned bits from the bottom of the pan. (If skipping the cognac, use a splash of water.)

Add the marinated vegetables and cook for about 5 minutes, until lightly caramelized. Season with salt and pepper.

5. Braise

Return the chicken to the pot.

Sprinkle the flour evenly over the chicken and vegetables, gently tossing to coat.

Pour in the reserved marinade, chicken stock, and bay leaf. Bring to a boil, cover, and transfer to the oven.

Braise for 60–75 minutes, or until the chicken is very tender.

6. Cook the Mushrooms & Pearl Onions

While the chicken braises, melt the butter in a large skillet over medium-high heat.

Add the pearl onions and cook until tender and lightly golden, 3–5 minutes. Remove and keep warm.

In the same pan, sauté the mushrooms until they release their moisture and begin to brown, 5–8 minutes. Return the pearl onions to the pan, toss to coat, season with salt and pepper, and set aside.

7. Finish the Sauce

Once the chicken is tender, remove the chicken and vegetables from the casserole with a slotted spoon and keep warm.

Place the casserole over medium-high heat and reduce the sauce for about 10 minutes, until thickened and reduced by roughly half. The sauce should coat the back of a spoon.

8. Assemble

Return the chicken to the pot and gently coat with the sauce. Stir in the chopped parsley.

Add the mushrooms and pearl onions either directly to the pot or portion them individually when serving.

How to Serve Coq au Vin

Serve with something starchy to soak up the sauce: tagliatelle, mashed or steamed potatoes, crusty sourdough, or golden croutons. A simple green salad makes the perfect contrast.

Bon apétit!

Happy sipping and savouring!

Comments